To Get to You

The night bus to Accra was leaving the station. Asare was in a ‘Pragya’ that was barely moving, a few metres away. He was supposed to be on that bus.

“Driver, stop stop.” He handed over a two-cedi note and jumped out of the tricycle, his change forgotten. With energy from his supper of fufu and abunuabunu soup still firing through his athletic thirty-five-year-old body, he sprinted across the street.

“Hey! stop the bus!”

Asare waved an arm around wildly, the leather bag, slung around his shoulder swinging along with it. As one would expect in a township, alert bystanders immediately took up his cry. The young boys, truck-pushers by day, and night, run up to the large bus, banging against its sides. The beast came to a halt, it’s break lights glowing red in the darkness.

“Thank you. Thank you.” He ran past them to the door of the bus. It opened slowly, and a young boy stepped out. Braa ‘mate’ was not happy.

“We told you to be here by seven. Why are you people like this?”

But Asare wasn’t listening. The boys were coming towards him, no doubt to receive their appreciation. He dug a hand into the back pocket of his jeans and tossed a crumbled two-cedi note towards them. They were ‘hailing’ him even before it hit the ground. And that’s when he remembered his one-cedi.

Too late.

Asare squeezed past the ‘mate’ and entered the bus, its cold air soothing his hot hot body. All eyes were on him. Asare smiled.

“Driver, I’m very sorry, wai.”

The bus lurched forward and he grabbed two seats just in time to steady himself. It veered around a small roundabout and soon cruised onto the main road.

Asare scanned the seat numbers as he inched forward. Ticket number 35… 35…

A thick hand waved at him. He waved back, walking up to the woman. She dragged herself to the window seat and he settled in.

“Thank you, maa.” Asare sank into the cushion and laid his head back. Cold air caressed his bald head. God, he was tired. But he was in. There was still time. It was now eight p.m. He would be in Accra hours before seven a.m.

No bagawaya.

“You must be tired.”

He shook his head. “Rough!”

He had come to town for a friend’s funeral; Darko, and old school mate had drunk himself to death. Good man, no self-control. Asare had known the funeral would take all day considering his relationship with the family. He had even planned to stay for the Sunday thanksgiving service. But all that had changed on Friday when she called.

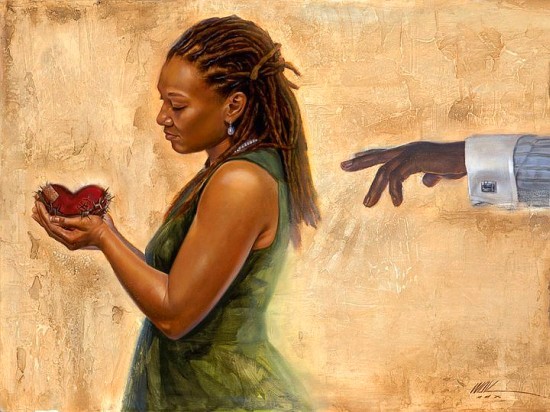

The face that popped into his head made him smile.

His baby girl.

“Good evening my brothers and sisters.”

Asare sat up. A young man was walking the aisle, a bible held up. Asare pulled out his wallet and opened it. In a few minutes, the man would start the sermon and there would be no time. He pulled it out and smiled again. The picture was defaced from a day he was beat by the rain. And there was a black ink spot. But she was still there, the love of his life.

Asare sighed.

She was everything. Just a glimpse of her, and all the stress of the week drained away. He couldn’t wait to see her, to wrap his arms around her. To hold her so tight she started to giggle. There was nothing in the world quite like her laughter. Nothing so light it just made a person want to just float around on a river all day.

“She’s beautiful.”

He turned to his neighbor, nodding.

“My Ghana’s most beautiful.”

The woman laughed, tapping him lightly on the wrist.

“Beloved, shall we close our eyes in prayer.”

Both passengers bowed their heads as the preacher plead the blood of Jesus over the road from Berekum to Accra and over the tires of the Bus.

“Jesus!”

Asare opened his eyes.

He had slept? He stretched. The last thing he remembered was something about Romans chapter three. But the preacher was no longer in the car. Where had they reached?

“Driver, why? Do you want to kill us?”

“Driver, what kind of carelessness is that?”

“Driver take your time oo. Yoo.”

He looked around at his surroundings, taking in the commotion. Everyone was talking at the same time. He caught a glimpse of Lil Wyn on the overhead screen. He turned to his right. Mama Rita, his neighbor, was fast asleep. He tapped a passenger in the seat across the aisle. The young girl pulled off her headphones and turned to him. Her tiny braids covered half her face.

“Why, what happened?”

“I think we blew a tire.”

Asare moved to the end of his seat. “Ehn?”

The girl shrugged, put her headphones back on. He looked up at the car’s clock. 12:00. They were in Konongo. There was still time. He rubbed his shoulders, no longer a fan of the air conditioning.

Both driver and mate had stepped out of the bus. Asare joined them, craning his neck as they pulled a toolbox.

“Mate, do you have a spare?”

The boy handed a spanner to the driver.

“It’s not the tire. We’re working on it.”

“How long do you think it will take?”

“Massa, give us time. I said we are working.”

Asare recoiled. The driver looked confident. They were three hours away from Accra. It wouldn’t be long. He opened his WhatsApp, started typing and stopped. She would still be sleeping. There was no need to worry anyone. He was going to be there, ‘live and colored’.

He sat on the ground beneath an electric pole, leaned against it and closed his eyes slightly…

“Kwadwo Asare!”

He shot up, rubbed the back of his hand across his nose.

“You, you can sleep anywhere, ehn?” Mama Rita shook her head.

He stretched. “Did they fix it?”

“No. These people? We are waiting for a car.”

He pulled his phone out and checked the time. Half past two. That woke him up instantly.

Asare strung his bag and run to the driver.

“Massa, kaa no aduru he?”

The driver stood Akimbo. “It will reach here very soon.”

From experience, he knew ‘very soon’ could mean in five minutes or five hours. And he couldn’t take any chances.

“Me se aduru he?”

“Massa to wo bo, wai. It’s on the way.”

Asare looked around the highway. Buses traveled at night all the time. And private cars too. It wouldn’t be difficult to find one. He walked a bit farther down the road, spotted a mini-bus.

“Accra, Accra!” He held up a hand.

The driver honked twice, then whizzed past him.

One down, many more to go.

Ten minutes went by, then thirty.

A Nissan Sentra stopped a few meters away, then reversed. Asare run up to the car.

“Madam, good evening.”

The driver nodded. “Going to Accra?” she said in English.

“Yes, please, Madam. The car break. Very important.”

She craned her neck towards the bus. A few of the passengers were staring now. He turned back to her, praying that God would touch her heart. That she could see the desperation so visibly scrawled across his face.

“What’s your name?”

Name. He knew name.

“Asare, madam. Very important.”

She smiled. “Asare, let’s go.”

He raised his hands in victory. “Thank you madam! I’m coming!”

He run towards the bus to share the good news, and recruit a passenger or two. Mama Rita would have none of it.

“Are you crazy, getting into that car?”

“Oh, it’s a woman oo. And I have to be in Accra early this morning.”

“Yes, but you’ll be no use to her dead. Just explain to her. I’m sure she’ll understand if you explain.”

Asare shook his head.

It wasn’t a question of if she would understand. Of course, she would. She loved him too, no question. But there had been too many times when she had to understand. The first time, it was a client who held him on his farm. The second time, he couldn’t turn away the money so he decided to extend his hours. Then there was the time when his boss had put him in a corner. Over and over, he chose other priorities. And each time, her pleas would tug at his heart.

He had called the day before to give her the usual: something had come up and he wouldn’t be there. Asare had braced himself for the heart-wrenching pleas. But this time, all she said was ‘okay.’

No crying, no pleading. Just ‘okay’.

That was his wake-up call: the absence of emotion in that single word. She had expected him to say ‘no’ and he had. He had told her enough times that she came second, at best. That she was not a priority. And he knew first-hand what that did to a person. He couldn’t let that happen to his Mimi. So, come rain or shine, he was going to be at the Adabraka branch of Holy Trinity Catholic church at 07:00 a.m.

He ran back to the car, waving at the passengers. They, of course, looked at him like a man who would feature on the six o’clock news as a victim of murder or kidnapping. He too had heard the news of such things happening. But there were still good people in the world. He was one of them. And this woman …

“Madam, your name?”

“Beatrice. You can call me Auntie ‘B’.”

“Oh fine, fine.”

Yes, Auntie ‘B’ looked like a good woman. But he was going to stay alert, just to be sure. So he prayed. It was a Sunday, after all. God would not allow anything bad to happen to him on his holy day. And he talked for all his was worth, fighting like a mad man to keep his eyes open, lest he wake up in some foreign land, headed for the slaughter.

“Asare!”

He opened his eyes. The car was not moving. There was light all around. Daylight. Beatrice was smiling at him.

“We’re here.”

He heaved a sigh of relief. ‘here’ was a short walk from his church.

“Madam, thank you so much.”

“You look relieved.”

He opened the door. “I’m just happy I made it in time.”

“You thought I was going to kill you.”

“Oh no. It’s just the other passengers. But I knew you were God-sent.”

“Well, you should have listened to them.” Auntie ‘B’ started the car.

“You’re supposed to be locked up in a room right now, awaiting execution. But I couldn’t stop thinking about that poor girl. It would be a tragedy if her father never showed up at her first reading in church.”

Asare swallowed.

Beatrice laughed.

He laughed.

Kwadwo Asare was a man wrapped around the little finger of a six-year-old. His was a condition, experts agreed was incurable. And he had known for years, right from the day she was born. One look into her eyes and he knew he would be hers forever. Whatever she needed would be hers. And whenever she needed him, he’d be there. He would ride on the back of a crocodile, swim across the Volta, and yes, take a chance on his own life. Even if it was to sit in a pew while she read Isaiah chapter forty-nine.

So, thriving on stolen naps, he walked into the church, looking forward to that laughter that would make it all worth it.

Photo by Renee Fisher on Unsplash