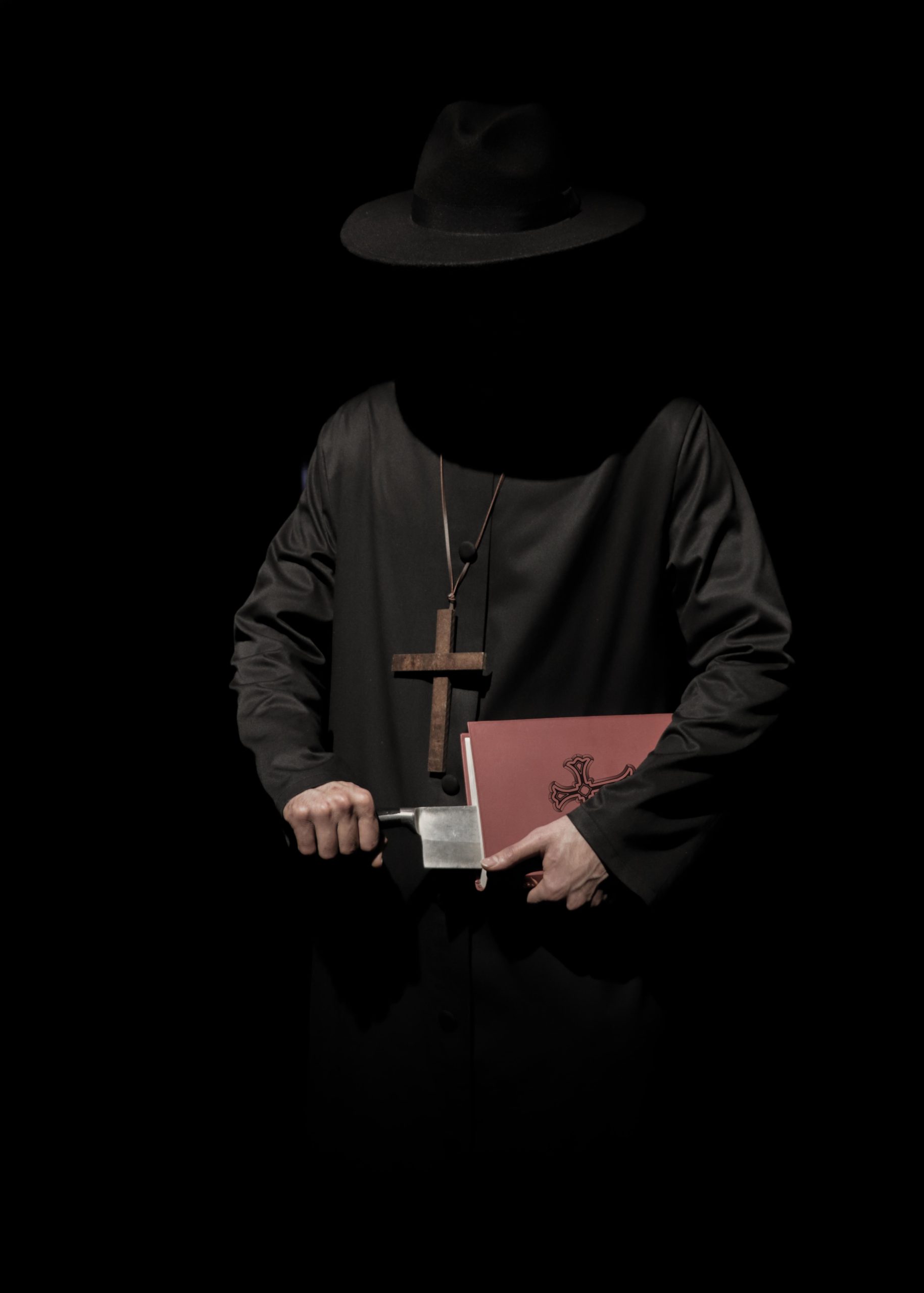

In the Name of the Father

It’s the first Sunday of the new year. In the town of Berekuso, parishioners of St. Mark’s catholic church, dressed in their Sunday best, yawn on their way to church. As always, the Christmas season has been a marathon of services, and the New Year mass had only been held the day before. Thankfully, the end is in sight.

But, it’s not all good news.

Behind the altar, the parish priest, Father Nimo, and Fr. Manasseh, his assistant, are seated, flanked on both sides by mass servers. Above them, a large crucifix hangs. It’s the last time both of them will be on the dais together. Their faces, covered by surgical masks, betray no emotion.

The undercurrent of unease is almost imperceptible.

The Liturgy of the Word:

1st reading.

2nd reading.

The gospel.

“The gospel of the Lord.”

“Praise to you, Lord Jesus Christ.”

With that, Fr. Nimo returns to his seat. Fr. Manasseh takes his place behind the lectern, gripping its sides. He takes his mask off, looking into the congregation. In less than an hour, He’s supposed to bid them farewell. But for now, he proceeds with his homily.

The sermon is refreshing, concise, crisp. There are no frills, no filler words. It’s not dessert, a sweetness meant to please. It’s a whole meal, a healthy serving of scripture, story-telling and exposition. It’s apparent to all he has learnt well from his time with the Parish Priest.

“ ‘Just as our bodies have many parts and each part has a special function, so it is with Christ’s body. We are many parts of one body, and we all belong to each other. In his grace, God has given us different gifts for doing certain things well.’ Everything we do is for the church. God sends us where we are needed. We don’t let ourselves get in the way, or envy our brothers if they can do something we can’t. Everything we do is for him alone.”

There’s intermittent nodding, laughter and wry smiles amongst a congregation painfully aware that this is his last sermon. The young priest, after a year in the town, is being transferred to another parish, by order of the diocesan bishop.

Behind him, at the altar, the parish priest rests his chin on interwoven hands. His eyes, old but sharp, are squinted, his thoughts concealed.

1st. Collection. Liturgy of the eucharist. 2nd. Collection.

The sendoff ceremony begins immediately after the collection boxes are emptied and returned to their place before the congregation. The wittty Cathechist Aforo is at the helm of affairs:

Show some love for the priest. Bring your money, bring your gifts. Say your goodbyes. Don’t say his reward is in heaven biaa. His reward is in your pocket. Show some love.

And they do. Men, women, young and old, they come up to the altar with balled fists and drop their notes and coins into the offertory box. There are white envelopes too. They bring them to the dais in their numbers and the catechist reads out names written at their backs.

After a word of appreciation to the congregation, he calls forward the youth group, who have a farewell of their own planned. Clad in white, they call out Fr. Manasseh. They have a present: a citation, which they read out. It’s a lengthy account extolling the many virtues of priest, and the work he has done.

The congregation nods in agreement. A few of the young girls are already crying. Fr. Manasseh stands still, listening. Behind his glasses, there are tell tale signs of tears.

And then for their final act, the lads break into a song they’ve rehearsed all week.

“God be with you till we meet again;

By His counsels guide, uphold you,

With His sheep in love enfold you;

God be with you till we meet again.

Till we meet, till we meet,

Till we meet at Jesus’ feet;

Till we meet, till we meet,

God be with you till we meet again.”

There’s not a dry eye in the church.

The transfer had come as a surprise to all. One year? It was the shortest anyone had ever stayed. They said the bishop needed him elsewhere, but rumor had it that was not the full story.

Fr. Nimo comes up to give his final words.

“We thank the youth for this wonderful display of love. I couldn’t hold back my tears either. Father Manasseh has done a wonderful job here and it’s sad that he’d needed elsewhere. But that’s how our work is. We go where God calls us. And God calls his people in different ways. Sometimes, we don’t understand it, but we just have to trust him.”

In the front rows, reserved for the elderly, Opanyin Nti blinks away a tear.

“I don’t think Bishop made the right decision with this one,” he whispers to his friend in the next seat.”

Mr. Opare adjusts his black and white cloth with a veined arm. “I don’t think the bishop had anything to do with this.”

“Didn’t you hear what father just said? The bishop decided to transfer the young man.”

“If a frog comes out of the water to tell you that the crocodile is dead, do not doubt it.”

Nti turns fully to his friend, whose nephew is a mass server, presently seated to the right of the priests.

“Tell me. What happened?”

Mr. Opare leans into his chair, sets his nose in the air. “Ever since the boy was sent here, things have not been the same. Fr. Nimo said it himself that he was doing good work. That’s why he appointed him as youth chaplain.”

“Ampa o,” Opanyin Nti whispers his agreement.

“The number of people who came for youth mass increased drastically. I’ve never seen anythng like it in this parish. Akoto tells me they see him as their friend. He attends their parties, and plays football with them. A whole priest. Why else do you think they were up there crying like orphans?”

Opanyin Nti nodded again. “So, if he’s done a good job, and it’s not that the Bishop needs him elsewhere, why is he being transferred?”

“From what I hear, they got too comfortable with him. They started going to him for everything, disregarding the normal order of things. And that didn’t go down well with some people.”

Mr. Opare turns his eyes to the altar. They narrow slightly. Opanyin Nti follows his gaze. They both stare for a moment. He nods.

“Ah. I see.”

“Let us go in the peace of Christ. The mass is ended.”

The two priests stand in front of the mission house, as parishioners trickle out of the compound. Friends say their goodbyes, families try to find their members, plans for church meetings are being finalized.

“Nice homily, “ Fr. Nimo says.

Fr. Manasseh waves at someone. “It was inspired.”

And then, deciding it’s time to dispense with the façade he turns to his Parish Priest.

“I could have done so much good here.”

The PP. smiles. “You can do good in Mpasa.”

“It was never my intention to ….”

“You will be missed, Fr. Manasseh. Go in peace.

The young priest says nothing. He looks around the parish he has come to love, and walks away.

Father Nimo looks around. At his parish. For a second there, things had gone out of control. There was a normal order of doing things. If that was not followed, things didn’t go right. He hadn’t sacrificed the future of the church for a personal grievance. No. He had maintained order, as it should be.

“Good morning, father.”

He blinks. The president and vice of the youth group are standing before him.

“Yes, Ellis. What do you need?”

“We want to discuss something with you. The program for the youth convention.”

The old priest holds back a smile.

Much better.

Photo by mahdi rezaei on Unsplash